For the longest time, I’ve been preoccupied with how buildings and architecture make us FEEL. That’s the reason I’ve spent months and years wandering the streets of cosmopolitan port cities.

I would stalk these streets with my camera, in search of historic-beautiful vistas that appear from out of nowhere and make me gasp; tangible remnants of the past that linger on sublimely as spectacle.

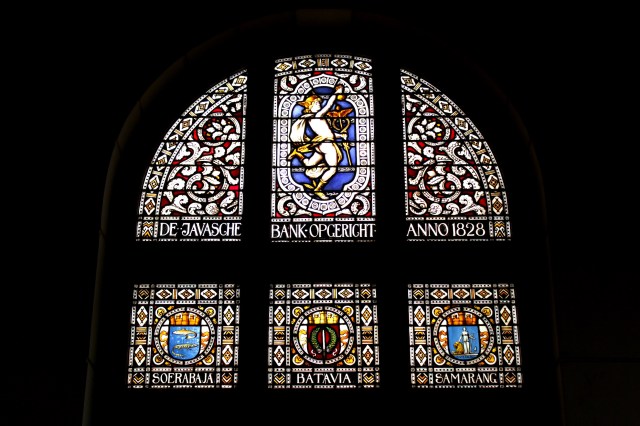

Glittering mosaics depicting Christ Pantokrator at the Monreale Cathedral in Sicily, for example… Or one’s first view of the Taj Mahal in Agra… A swirling dragon on the ceiling at the Kenchoji Temple in Kamakura… A stained-glass window at the former Javasche Bank Building in Kota Tua, Jakarta…

With my camera, I’d attempt to capture the sense of immensity imbued in these vistas. But alas, the camera’s lens is limited, being merely able to grasp the visual, whereas immensity is invested in experience — it is spatial and multi-sensory.

Photographs of architecture (or art, for that matter) cannot convey the specific array of feelings that the architect (or artist) intended for their work, and has invested in its material form. You cannot be awestruck by a photograph or a digital / virtual reproduction of the real thing. [The exception is, of course, when the work of art itself is a work of photography or a digital/virtual reality/multi-media installation.]

To be awestruck, you have to encounter art and architecture in person; engaging fully with your senses (and beyond the usual five).

This is because the state of being awestruck – or MOVED TO GASP – is a bodily one. It is a physical, chemical and also primal reaction. The ability to be moved or touched emotionally by something is what makes us human.

There is a word that describes the propensity of a work of art or architecture to move or touch (in the emotional sense) – AFFECT.

* * *

A friend of mine once said I had a “flair for affect”. That my writing was “affective” – it had the power to move.

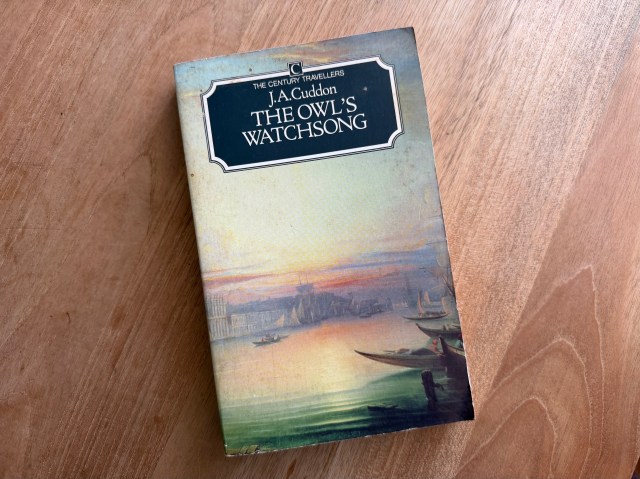

One of the highlights of reading THE ROMANCE OF THE GRAND TOUR – so he and some of my readers have said – are the vividly-painted scenes set in each of the port cities I journey to, and which are able to convey not only the essence of each city, but also a feeling. Scenes set in the past are invariably suffused with different degrees of nostalgia, from child-like wonder, to quiet contemplation, to saudade (sense of loss).

And indeed, I write with the conscious intention of conveying not only fact, but atmosphere and sentiment.

I affect (note choice of words) the voice and persona of a turn-of-the-century writer-wanderer, who, ensconced in the corner of the historic hotel he’s shacked up in, pens notes by way of a pencil to a well worn-out notebook, of minute details he recalls in his peregrinations through the city’s old town that morning.

It could be how the light had fallen on and illuminated the elaborately-decorated plaster cornice of a shophouse building in Amoy. Or a passing comment overheard as he walks through the bustling fish market in Goa. Or the lingering scent of melati in the old but rambling mansion he has had the privilege to enter and explore in Semarang.

All these details impart a nugget of sentiment in his writing. And he weaves them all into a larger tapestry of experience, conveyed through words.

* * *

My friend – the same one – told me that my flair for “affect” also extended to my work at the museum. That my time there (and my legacy) was defined by gallery displays and special exhibitions that were “affective”: i.e. designed to move.

That is a fact too.

One of the “Key Performance Indicators” I affected (again note choice of words) for our curators, designers and exhibition professionals was for our exhibitions and displays to be “gasp-inducing”. In other words, somewhere in the course of the exhibition or display, there would need to be one – or better yet, several – moments that MOVE the visitor TO GASP.

There’s no magic to these gasp-inducing moments in the show. These are entirely calculated; the product of design intent and technical excellence.

By design intent, I mean having a clear design brief. The sort of design briefs I insisted on at the museum had to meet the following demands: 1) the design for the show needs to be completely original, like nothing anyone would have seen in any other museum anywhere on earth; 2) they had to convey three design essences, two of which were aesthetic, and one affective.

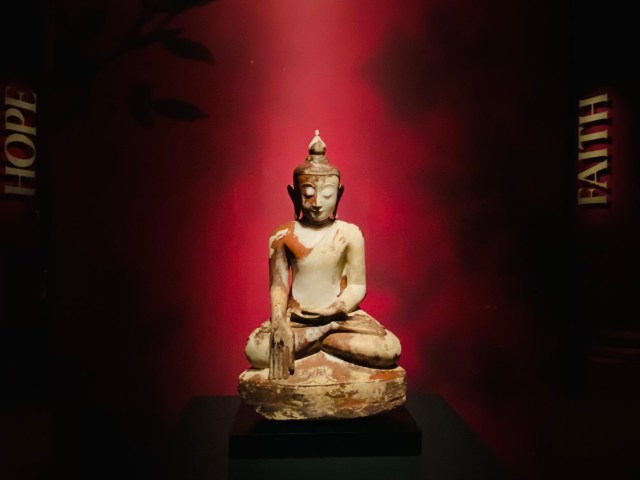

Technical excellence pertains to 1) placement of the object; 2) setting (i.e. backdrop, or scenography) and most importantly 3) lighting. These three aspects are highly variable, but in the hands of expert professionals, they may be manipulated in a manner that makes the object and the entire exhibition itself emanate presence and lifeforce. The word I tended to use was semangat, or “spirit”.

My preferred Design Brief format was applied for the first time to the ANGKOR: EXPLORING CAMBODIA’S SACRED CITY exhibition in 2018. I asked that the exhibition design captured and blended the following design essences: 1) 1920s Art Deco (aesthetic); 2) Khmer Art & Artistry (aesthetic), and 3) A Sense of Exploration and Discovery (affective).

On paper, the exhibition design conveyed all three brilliantly. The excellent curatorial, exhibitions and lighting professionals at the museum executed the design with great flair.

I knew that the exhibition design was a success quite early on in the show.

During the previews, I happened to take a very, very important guest on a private tour. This was a man who professed to favour the sciences and economics; by all accounts, a rather staid and severe personality.

As we turned the corner into the final gallery space – where the largest and most impressive pieces of Khmer stone statuary were lined up in an sacred, orderly procession extending to the furthest-most wall of the gallery – he gasped audibly and said “Wow”.

His veneer of severity had been broken, and there were almost tears in his eyes.

At that very moment, I also decided that every special exhibition henceforth had to have these moments of the sublime; these moments of rapture.

* * *

There is a tangible value to THE GASP. Permit me to share a story.

Late in my tenure we refreshed one of our major permanent galleries of sacred art. The exhibition design looked good on paper. But when it was executed, there was a fatal flaw to it: it cut off the visitor’s view to the far wall of the gallery, effectively negating any sense of immensity that I’d hoped the space would convey.

I sent the design back to the drawing board, insisting that the showcases be torn out and the re-opening of the gallery be delayed.

My justification was as follows.

It was Gala Season at the time, and I was taking many potential patrons on private tours of the gallery. As they turned the corner to enter this particular gallery, I needed them to gasp in wonder because when they did, they would almost certainly agree to buy a table for the gala.

“I need them to be moved to buy a table!” so I told our bemused lead curator and exhibition professional. “I need this view to be a $28,000 vista!”

I got my way. A new design for the gallery was put in that didn’t block the visitor’s view to the far wall. Once he or she steps into the gallery, they would palpably feel the vastness and immensity of the space, and the play of shadow and light hinting at the ineffable.

I got a call, not long after, from a major patron, who wanted to make a substantial gift towards the gallery, by virtue of that sense of the sublime – the suggestion of divine presence – in the space. This had greatly moved him and others of his community.

The scale of the offered gift was immense. Let’s just say it was way more than 10,000% (yes, that is correct; there are 4 zeros) of the value I had affixed to this specific vista in the gallery.

That, so I thought to myself, was the most tangible proof that AFFECT had VALUE.

To put it bluntly: when they GASP, they GIVE. When you touch someone’s heart, they open their hearts to you, expansively and in ways you least expect.

I think of the Chinese word for “move” (in the emotional sense): 感动 gǎndòng. This is a far more eloquent word than its English equivalents, being a combination of the character for “emotions”(感) and that for “movement” (动). There is causal implication here: the word structure itself suggests that affect inevitably leads to action.

Therein lies the power of art and architecture.

* * *

It isn’t all calculated, of course. My interest in affect is not driven at all by the need to sell books / exhibitions or raise monies. That’s the side effect of a job well done.

The creative pursuit of AFFECT is essentially a pursuit of excellence.

I write in a manner that touches people’s hearts because I believe this to be one of the hallmarks of good writing. Likewise, I demand that exhibitions & programmes I helm have the ability to 感动人 gǎndòng rén (move people), because this is the hallmark of a great exhibition or programme.

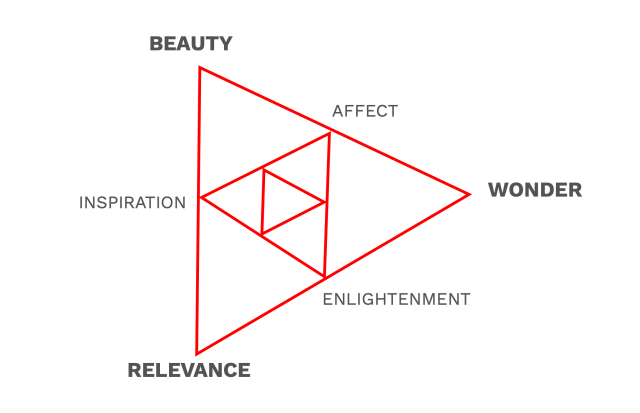

Affect can’t be the sole outcome of creative endeavour, of course. One also needs to convey an idea, to change the way people see the world and themselves, i.e. to enlighten. But Affect is of equal importance to Enlightenment, at least in my book. Indeed, Inspiration is what ensues when Affect meets Enlightenment.

The affect I pursue lies somewhere between BEAUTY and WONDER – which were two out of three of the museum’s brand essences; that which must guide and inspire all of the institution’s creative endeavour.

The third brand essence was RELEVANCE – between this and WONDER lies Enlightenment. And finally, between RELEVANCE and BEAUTY lies Inspiration.

Thus is the triangle complete.

* * *

Interested in better understanding the relationship between affect and architecture, I requested – from the same, very kind friend of mine (you know who you are!) – a suite of academic readings that attempt to dissect and examine feeling (all fleeting and spontaneous) by way of reason (all theory and criticism).

Many of these papers tend to cast affect in a somewhat negative light. To wit: affect is not really a good thing. One must see past and through it to the power structures that undergird and precipitate it. One shouldn’t be so naive as to fall blindly for it. Affect is a form of control.

Another underlying sentiment seems to be that affect (being of sentimentality and the heart) is misplaced in the realm of academia (being of criticality and the mind).

Thankfully, I stumbled upon a recently-published book that engages with the question of affect in a more neutral, almost positive manner. This is the excellent Architecture and Affect in the Middle Ages, by Paul Binski, Emeritus Professor of the History of Mediaeval Art at Cambridge University.

The book was a slim and impactful tome; wonderfully engaging and easy to read. I was tremendously moved.

The book’s main argument (if I may summarise in a far too brutishly efficient manner) is that architecture – especially religious architecture – is inherently affective. Places of worship are built to function as symbols, appealing to the (collective) imagination and thus able to provoke specific feelings associated with divine presence – a sense of immensity and grandness or peace and serenity, which in turn precipitates awe, wonderment, rapture.

With a focus on Christian – and to a certain extent, Islamic – religious architecture in the Middle Ages, the author points out that societies regarded faith and realms of the imagination as inextricable parts of everyday life. They believed that the ephemeral had impact on the tangible and material.

Societies today are dramatically different than before. Today’s prevailing value systems and ways of thinking – which are critical, scientific, capitalistic – thus struggle with attaching value and significance to “the complexity of emotional experience [that these buildings] engendered.” (Binski, 5)

A more useful starting point (in the critical analysis of these feelings) would be to evaluate the affective power of architecture from the perspective of the value systems of the time in which they were built. Along the way, perhaps we will acknowledge too, that architecture (and art) still have the power to affect us in the contemporary day.

“The way buildings move or affect us – a word chosen carefully – is all part of experience. Architecture is neither a representational art nor for that matter an entirely abstract one. Like the medium of music, it has no subject matter, or propositional power like language: it is itself. But one claim [of this book] is that buildings can still show us something, and so convey an affective “charge” capable of arousing the passions, changing our experience and so ultimately our beliefs and actions. A building’s human backstory may not entail just shapes and colors, spaces, forms, and light, but also the force of a tremendous human drama. Indeed […] for many people music and buildings are just as moving as language, if not more so.” (Binski, 5)

* * *

Art, Design and Architecture are affective, by nature. They are supposed to evoke/provoke/invoke all sort of emotions: joy, sorrow, anger, love, nostalgia, wonder, bewilderment, rapture, joy, magnificence, immensity, solace, sublimeness, disgust, etc.

What’s most interesting to me in the study of Affect is the human labour and ingenuity behind its construction. In other words: I’m curious as to how the lowly artist, architect or crafts(wo)man was able, with mind, heart and hand, to invest the corporeal form of their work with elements of the ineffable.

How does one invest brick and mortar with spirit and soul?? What are the skillsets and tools required? What values and belief systems? What techniques of craftsmanship and problem-solving? What flights of fancy and the imagination?

This – the Craft of Affect – is worth deeper exploration.

My next related question would be: how would one value Affect? What are the frameworks with which to tangibly measure the $$ value of emotions?

Affect clearly has tangible, monetary value. Consider the luxury industry, which relies on the affective quality of its product. Inordinate amounts of investment are made into affective elements such as craft, heritage, branding and story-telling. The more a luxury product is able to move or touch the consumer (emotionally), the more the latter is willing to pay for it.

How does one quantify the delta (pertaining to affect)? Or the competitive advantage affect affords (to luxury brands, for example)? What are the Returns on Affect, particularly for Affective Industries?

Better understanding the Craft of Affect + identifying metrics for the Returns on Affect = ascertaining the tangible value of creative endeavour. To wit: what quantifiable figure should we attribute to that ingenious application of mind, heart and hand towards investing the corporeal with the ineffable?

Or in simpler terms: what is the value, ultimately, of Art, Design and Architecture? Might we need to attribute tangible numbers in order to place these fields on a more equal footing, say, with the domains of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM)?

For inspiration, we look skywards – awestruck – upon the muqarnas-vaulted ceiling of the architectural masterpiece in which we stand…

Reference:

Binski, Paul. Architecture and Affect in the Middle Ages. Oakland: University of California Press, 2024.