It’s been a busy month and a bit. Short spurts of travel. Loads of things happening that have import on my future. Plus, I was also ill for a couple of weeks. So I had to pause on my journey of reflection. I’ve also decided to take things a little easier on this second half of the journey.

Now that I’m back I think it’s time I tackled the most important thing that happened to me last year – actually probably the most important thing I’ve achieved in my life thus far. This was the publication of my book, THE GREAT PORT CITIES OF ASIA: IN HISTORY.

The book was a culmination of 12 years of journeying, photography and research into the history, art, architecture, cultural heritage, material and popular culture of cosmopolitan Asian port cities.

I was so tired after stepping down from the job last year, I didn’t do as much as I should to promote the book. I’m trying to rectify that… Starting with this long-delayed post.

But first…

* * *

Since stepping down from the museum, I’ve been trying to clarify what exactly I am: what is my professional “title”, so to speak.

Yes, I’m an AUTHOR. I’m published. I’ve got a few books under my belt. But author doesn’t quite describe all that I do.

I tried HISTORIAN. But I’ve never seen myself as a historian, per se. Historians work in the realm of text and narratives. I’m interested in objects, buildings, aesthetics and intangibles; and what they reveal about the past and about how people lived and regarded themselves. Oh, and I hate linear narratives. I like discrete stories within larger, complex, interconnected, often circular, flows.

Though I worked at a museum, I wouldn’t describe myself as a CURATOR. I’m sure I’d be able to curate an exhibition, if I wanted to. But I never got a chance to. So I can’t back up that claim.

And while I’m capable of writing academically – I have written a peer-reviewed primer on Heritage (that remains a primer today) – I wouldn’t consider myself an ACADEMIC. My strength and interest is in STORY-TELLING: distilling dense, academic treatises into engaging-enjoyable, bite-sized nuggets of human drama.

I style myself a WRITER-WANDERER. But it would never do to call myself that professionally. It would probably raise eyebrows; have me seem far more eccentric than I actually am.

I mean… I am eccentric. But no one needs to know. 🤣

The mot juste as to my professional identity came courtesy of the (wonderful) editor of my book, THE GREAT PORT CITIES OF ASIA: IN HISTORY.

She said, “Kennie, this is not a history book. The title is misleading. This is a work of cultural history.” She also suggested that the title of the book be THE GREAT PORT CITIES OF ASIA: A CULTURAL HISTORY.

As much as I agreed this was the PRECISE description of what the book was, my publisher and I both decided that for a title, this was unwieldy and a little too academic. We left the title as it was.

But the fact remains. The book is a work of cultural history: wherein one tells history by way of the arts, architecture, heritage, music, literature, performance, music, dress, food, ways of living, etc.

And if the book is a work of cultural history, then I am a CULTURAL HISTORIAN. I realise I had also adopted this approach – of using culture as the frame by which to examine the past – in my earlier book, SINGAPORE 1819: A LIVING LEGACY.

So there it is! ME = CULTURAL HISTORIAN.

To celebrate my newfound professional identity, I dashed out to get myself a new namecard!

But back to the book…

* * *

The one big distinguishing element of THE GREAT PORT CITIES OF ASIA: IN HISTORY is precisely the fact that it is not a straightforward history book.

In structuring the flow, I was inspired by historic travel journals; in particular, the rihlah, or “Itinerary” of the great Maghrebi explorer, Ibn Battutah, who lived and journeyed across the known world in the 14th century CE.

So the book is, in fact, best described as a sort-of wide-eyed first-person account + epic, alternately hapless and swashbuckling romp across time and geography (i.e. the vast expanse of the Indian Ocean and maritime Asia).

And I – the omniscient narrator – play the role of a latter-day Ibn Battutah, or more accurately, a 21st century Frodo Baggins foolhardily setting out to seek truth and adventure.

It also doesn’t conform to a linear narrative. Yes, it runs more or less chronologically through time. But the structure of the book is better described as a mesh, and a psychedelic one, at that.

Characters, ideas, themes and scenarios recur along the way. Key concepts that belong in and would illuminate early chapters are only introduced and explained in the later ones. There are vividly-coloured nuggets of historical information popping out from the page everywhere you look (often accompanied with illustrations). And the last section of the book circles right back to the very beginning of our journey.

There are other unique qualities that serve to differentiate this tome from other worthy competitors, and provide you with the reason to procure your own personal copy without further ado. [Though the much-better First Edition hardback is already sold out – only the paperback version is available now.] 😜

For example, this is a re-telling of the story of a globalised Asia, from the perspective of its port cities and the sea, rather than its terrestrial kingdoms and the relentless succession of empires. It is a networked approach to exploring Asian history, which has often been cast in terms suggesting introversion and stasis.

I’ve done a lot of work in referencing and making accessible a vast (and often obscure) body of research and new ideas by many thinkers, academics, curators and experts in a multiplicity of fields. The book is thus also multi-disciplinary in nature. It(re-)tells history by way of art-in-museums, monuments, architecture, literature, flora & fauna, food, fashion, popular culture.

The book is obsessed with people and what they get up to. It is populated with a huge cast of historical characters, some familiar and some not quite so. It paints a vivid picture of the rich and strange cultural traditions of the many port city communities of Asia and the Indian Ocean, and how they have connected in the course of millennia.

In keeping with prevailing discourse in the museum world, I’ve made a concerted effort to de-centre traditional colonial narratives and spotlight perspectives of Asian agency, while still ensuring fairness in treating the complex legacy of colonialism.

Finally, there is the epic scope of the book itself, which is unprecedented and, quite honestly a wee bit insane. But therein lies the fun.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Borobudur_ship#/media/File:Borobudur_ship.JPG%5D

* * *

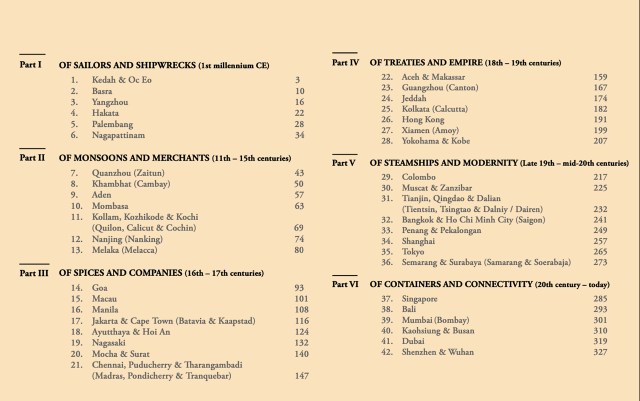

The book takes the reader on a journey through 60 port cities across maritime Asia and the Indian Ocean world. There are 6 sections, 42 chapters and some 300 pages in total. Certain liberties are taken with regards to geography: I include the Swahili Coast because this part of Africa was intricately enmeshed within networks of trade with Asian peoples in the Indian Ocean.

The timeframe our journey takes in is just as sweeping as its geography. We reach back some 2000 years to great port cities of late antiquity and forward to the great port cities of today in our journey. Along the way we take in the pre-colonial and the colonial period.

I fought hard with my publisher to include a section set in the contemporary day, because I wanted to make a point that the cosmopolitan Asian port city is a timeless phenomenon and that the great Asian port cities of today are not very different, in essence, to those of a thousand years ago.

We begin with a tale of sailors and shipwrecks from the early centuries of our Common Era to the turn of the 1st millennia.

During this time, Indian, Malay, Arab, and Persian merchants navigated the monsoons in their expertly-made dhows to trade in silks, spices and other items, and to spread faith and culture across the Indian Ocean.

Archaeology assists in giving us an impression of the times, with one spectacular find, the Belitung Shipwreck (at Singapore’s Asian Civilisations Museum), linking the stories of a few port cities.

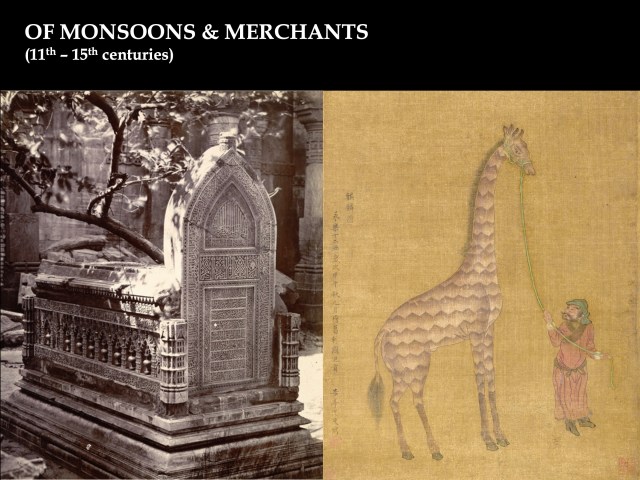

Our tale of monsoons and merchants continues on till the 15th century.

By this time, the Indian Ocean is a “Muslim Lake”, and Arab – later, Gujarati – seafarers expand their networks of trade down to the Swahili Coast and across to India and Southeast Asia.

The Chinese too, venture forth on the high seas during the Song, and later on, the Ming, Dynasties; and for a brief moment, Melaka blazes in splendour as possibly the greatest port on earth.

Intra-Asian trade is disrupted first by the Portuguese in the 16th century, and other Europeans subsequently, in a tale of spices and companies.

This incursion of the Europeans was precipitated by the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans, the sudden shortage of spices, and the stranglehold Venice held over these luxury items.

The entry of European powers in the Indian Ocean kicked off a struggle for dominion over global trade. In the meantime, Asian merchants – Chinese, Japanese, Gujaratis, Arabs, Turks – find ways to co-exist with these would-be interlopers.

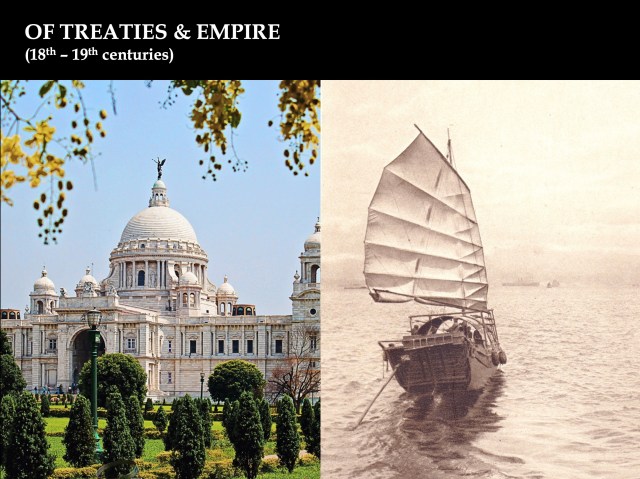

At the turn of the 18th century, the Age of Imperialism began. Trade became inevitably a tale, also, of treaties and empire.

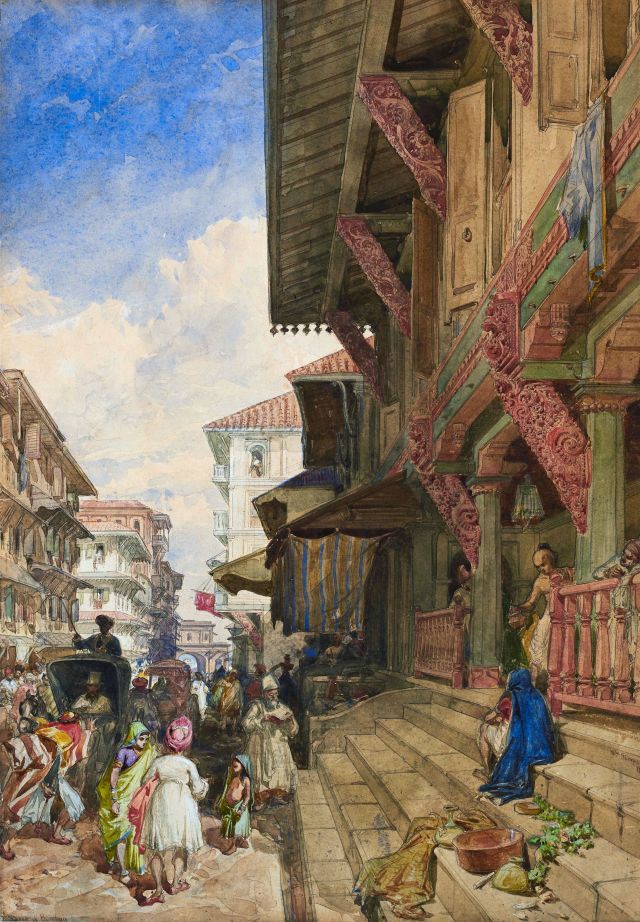

Port cities in Asia took on the cast of being colonial outposts, even as these cities resisted or adapted to colonial domination. In India, the British Raj rears its formidable head and goes for the jugular. In East Asia, Europe and America take on China and Japan.

By way of gunboat diplomacy, the Opium Wars, and a series of unequal treaties, so-called “treaty ports” were forced open for trade, precipitating the European powers’ metamorphosis into global empires.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victoria_Memorial,_Kolkata#/media/File:Victoria_Memorial_Hall,_Kolkata.jpg (Image cropped) | Historic postcard depicting a Chinese junk in Hong Kong. Author’s Collection.]

The 19th century bore witness to major technological advances that impacted travel and everyday life.

The opening of the Suez Canal revolutionised long-distance travel, and large-scale tourism to Asia became a reality. A tale of steamships and modernity sees the port cities of Asia becoming crucibles of new creative expressions and new ways of living, even as advances in technology aid in the consolidation of Empire.

The Age of Modernity would reach its horrific zenith with World War II and the subsequent fall of colonial empires.

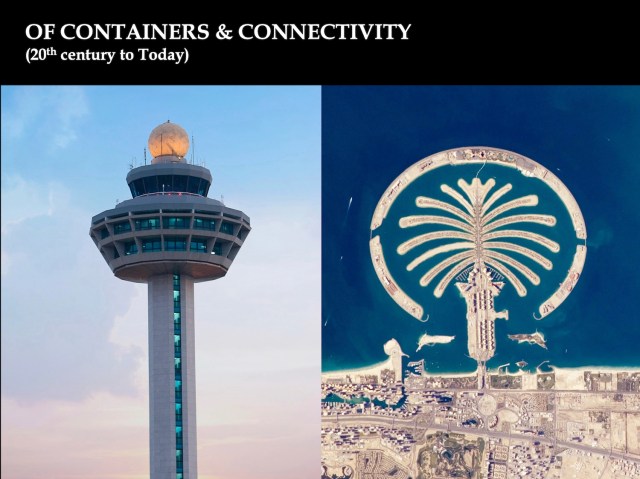

Finally, our journey ends in the contemporary day with a tale of containers and connectivity. We visit port cities that dominate trade and tourism today, and examine contemporary issues pertaining to economic development.

Singapore features here, alongside a few other comparable port cities across the extended Indian Ocean region, including those of the Asian Tigers of the 1980s and ‘90s, as well as later upstarts, Dubai and Shenzhen (a digital and technological “port”).

Most recently, the port city of Wuhan, China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and the Covid-19 pandemic, have prompted reflections on global trade and travel.

* * *

I’ve been frequently asked if I’ve travelled to all of the port cities in the book. And the honest answer is No. At present, I’ve only been to some 40 of these cities. I’ve got 20 more to go.

What I hope to do is to travel to every single one of these cities to experience, photograph, document cultural and heritage sites, in an obsessive and perfectionist bid for “completion”. I did quite a bit of that last year, which got me to 40 cities. I gotta keep going!

In the meantime, I’m also going to work harder at promoting the book. A couple of weeks ago, I was invited to deliver a lecture featuring Part II of the book – ON MONSOONS AND MERCHANTS.

The response from the audience was very positive. I myself thoroughly enjoyed the process of putting the lecture together. It was good to know that after a year retreating from society and the world (隐居), I could still hold an audience well.

Thus, I shall re-emerge to seek more opportunities to speak. Ideas welcome.

See y’all very soon. 🤞🏼